Note: The best book about Camden Harbour that I’ve ever read is now available here.

Readers scanning the eastern Australian newspapers of 25 August, 1864, would have seen reports of the latest situation in the American Civil War (“Desperate fighting near Spottsylvania courthouse”), along with the Maori wars and the Dano-German dispute. They would also have seen: “Western Australia: Intelligence from Perth to 26 July . . . the principal topic of the day is the proposed settlement of the Northern country. The reports of Grey, Martin and Panter leave no doubt as to its extent and fertility.”

______________________________________

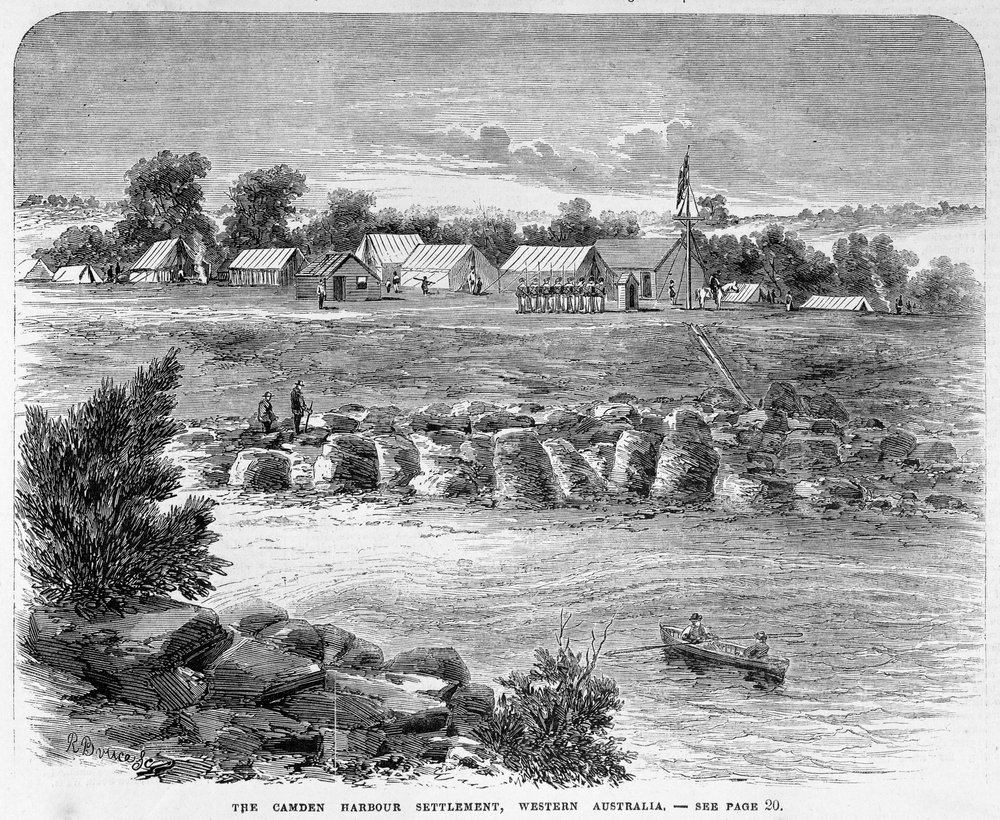

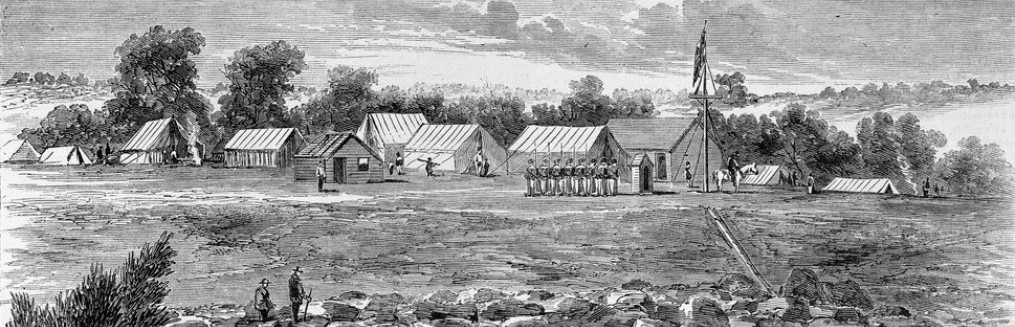

Camden Harbour, in Australia’s West Kimberley region, is closer by 2,000 kilometres to Koepang in Timor than it is to the Western Australian capital of Perth. It is still in the 21st century inaccessible to all but the most determined adventurers. At the height of its 12-metre tides it is to an inexperienced eye a superb shelter for shipping.

From the Dreamtime, Aborigines roamed its shores and drew wondrous, glowing paintings in caves not far inland from its mangroves. They fished, they lit fires to encourage new growth in the native grasses which in turn encouraged animal and bird life for them to hunt. When the creeks dried under a burning sun, they knew where rock pools and springs hid reserves of cool water.

I have traversed large portions of Australia, but have seen no land, no scenery to equal it.

Yet it has defied settlement by whites. Native grasses and weatherbeaten red rock were not something early farming settlers could cope with. They were also unnerved at ebb tides when the huge drop of the receding sea uncovered thick, blue-grey mud and the nearest green bushes revealed themselves as twisted mangroves.

God only knows how many of us will be spared or how many more will be left behind to take our final rest on Sheep Island.

However, the very first white explorers – who led the way for the farmers – were not dismayed by the awesome drop of a few tides. Those who came after the monsoons were more impressed by the rolling green ranges that lay beyond the top of the sandstone cliffs lining part of the harbour. It seemed a gateway to fine pastoral country. They saw their hopes confirmed by expeditions inland and reported back to their governments and backers that here was fine land for the taking.

But 2,800 kilometres from Perth by sailing ship – and a climate and land they had never experienced – proved a formidable barrier to others . . .

Their dramatic history is told in There Were Three Ships – the story of the Camden Harbour Expedition 1864-65, by Australian writer Christopher Richards. The award-winning book was first published in 1990 by University of Western Australia Press and is now in its fifth reprint.

Now an ebook on Amazon Kindle, Apple iBooks and Barnes&Noble.

Print edition available at good book shops between the 15th and 17th parallels south latitude:

Also at Outback specialists Westprint Maps.

![The parade ground for "pensioner" soldiers and government camp, led by magistrate Robert John Sholl, was on top of the promontory above the cliffs in the background. [Picture: Tim Willing]](https://camdenharbour.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/camden-parade-ground.jpg)